Welcome, Class 8 students, to another exciting blog post on the subject of Social Science! Today, we delve into the intriguing chapter of Education and British Rule. As we explore this significant period in history, we will uncover the impact of British rule on education in India. From the establishment of English-medium schools to the introduction of new educational policies, the British era left an indelible mark on our education system. Join me on this enlightening journey as we unravel the complexities and consequences of education under British rule. Let's dive in!

Introduction

In the earlier chapters you have seen how British rule affected rajas and nawabs, peasants and tribals. In this chapter we will try and understand what implication it had for the lives of students. For, the British in India wanted not only territorial conquest and control over revenues. They also felt that they had a cultural mission: they had to “civilise the natives”, change their customs and values. What changes were to be introduced? How were Indians to be educated, “civilised”, and made into what the British believed were “good subjects”? The British could find no simple answers to these questions. They continued to be debated for many decades.

Education in India in pre-colonial times

Let us look at what the British thought and did, and how some of the ideas of education that we now take for granted evolved in the last two hundred years. In the process of this enquiry we will also see how Indians reacted to British ideas, and how they developed their own views about how Indians were to be educated.

- The earlier system of education was very different from what the British introduced.

- Earlier, boys were taught at home or in pathshalas and madrasas. Girls mostly did not receive education.

- The educational institutes were started by teacher or guru or maulvi.

- When William Adam in 1830 was given task to report about progress of education in indigenous schools, he found over 1 lakh of pathshalas in district of Bengal and orrisa.

- The pathshala system was very flexible. In pathsalas there were no

- -> need to buy and read any prescribed books.

- -> fixed fee, fixed building, specific seating arrangements, blackboards, annual examinations, groups division based on age or class, timetable table for class.

- The class was conducted below a tree and in vernacular language orally.

- Guru would take fees from students based on their parent ‘s income.

- Pathsalas often remained closed during harvesting seasons because children of peasants also came to study and had to go to field for assiting their parents.

- In 18th century, English education was introduced by charity schools in madrasas in Madras, Calcutta and Bombay

- The Charter Act of 1813 allocated funds to encourage education in India.

- Since the medium of teaching was not specified , there arose a conflict where some thought that native languages like Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic should be used while others thought that western education should be imparted to people through English language.

- The person who supported native language as a medium of teaching were called Orientalist.

- The person who believed that English should be used as medium of teaching were called Anglicists.

Orientalist

Orientalist

- William Jones in 1783, arrived in India. He was a linguist (Someone who knows and studies several languages)

- He had an appointment as a junior judge at the Supreme Court that the Company had set up. He had studied Greek and Latin at Oxford, knew French and English, had picked up Arabic from a friend, and had also learnt Persian.

- At Calcutta, he began spending many hours a day with pandits who taught him the subtleties of Sanskrit language, grammar and poetry. Soon he was studying ancient Indian texts on law, philosophy, religion, politics, morality, arithmetic, medicine and the other sciences

- Jones discovered that his interests were shared by many British officials living in Calcutta at the time. Englishmen like Henry Thomas Colebrooke and Nathaniel Halhed were also busy discovering the ancient Indian heritage, mastering Indian languages and translating Sanskrit and Persian works into English. Together with them, Jones set up the Asiatic Society of Bengal, and started a journal called Asiatick Researches.

- In order to understand India it was necessary to discover the sacred and legal texts that were produced in the ancient period. For only those texts could reveal the real ideas and laws of the Hindus and Muslims, and only a new study of these texts could form the basis of future development in India

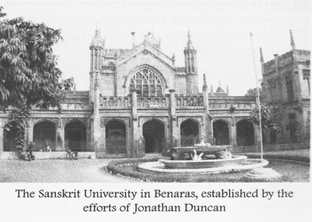

- With this object in view a madrasa was set up in Calcutta in 1781 to promote the study of Arabic, Persian and Islamic law; and the Hindu College was established in Benaras in 1791 to encourage the study of ancient Sanskrit texts that would be useful for the administration of the country.

.png)